Sri Lankan gems: the congealed tears of the Buddha

I confess to be a lover of gems. I know what you’re thinking – she’s just another female chasing bling and that’s a fair call. In my defence, however, it’s not a love for any gem. I’ve never cared much for the De Beer’s bandwagon for instance. Diamonds may well be forever, but their singular, white luminosity leaves me cold and somewhat bored. I prefer the drama which colour ignites in a rock and the way in which different chemistry and impurities uncovered by light can produce beauty of kaleidoscopic diversity. For this affliction, the blame lies firmly at the feet of my Sri Lankan heritage.

Most Sri Lankan gemstones are from gem-bearing gravel known as illam. The gravels are washed with the hope of revealing a treasure within the heavier material left behind in the miner’s hand. Photo by Andrew Lucas.

If you lived in Sri Lanka in ancient times, you’d probably know that its rivers were paved with gems. At least that’s how one of my uncles once described it to me as we were swimming in the Menik Ganga (literally “Gem River”) near Kataragama following a trip to the famous temple there. We started foraging in the river bed for signs of jewels. Every one of us thought that we each had struck gold (is there an equivalent expression for gems??) as we gathered a small mountain of pebbly river rocks of differing hues and heatedly debated their worth. Alas, they were all duds. Or at least that’s what we finally agreed that day, much to the relief of my uncle who had visions of having to reload the van with doubtful river gravel for the trip home. Uncut and unpolished, the real gems probably just blended into the murkiness of the river flowing beneath the gaze of our untrained eyes.

Menik Ganga - tributary at Ranugalla

It’s the ancient languages which bear testimony to my uncle’s description, each translating a description of Sri Lanka to be “The Island of Gems” with the scale and grandeur of its gem abundance being recorded as part historical fact and part mythology. The astronomer Ptolemy wrote about beryls and sapphires as Sri Lanka’s prime jewels. The traveller Marco Polo waxed lyrical about the streams of rubies, sapphires, topazes, amethyst and garnet and how the then Sri Lankan king possessed a ruby which was the thickness of a man’s arm and brilliant beyond description. The Chinese, who were long-time traders in Sri Lanka and purveyors of their own kind of jewels in fine teas and silks, were so marvelled by it all that they believed Sri Lanka’s gems to be the congealed tears of the Buddha.

The real power behind gems however is what they reveal about the dynamo that forged them: Planet Earth. And Sri Lanka can thank the turbulence of Earth’s prehistoric geological activity dating back to Precambrian times for its gem bounty. The metamorphic forces which built the world’s mountains and tore up the super-continents of that era also created the serendipitous by-product of gems. The Sri Lankan teardrop of land is a lasting remnant of that lottery of intense activity with about 90% of its underlying rock structure being high-grade metamorphic rocks and about a quarter of that being potentially gem bearing. It’s an astonishing fact that nearly 70 varieties of the world’s 200 minerals classified as gemstones are found in Sri Lanka.

You won’t be surprised to know then that when I’m in Sri Lanka I’m like a moth to a multi-coloured, luminescent gem flame. I’m always poking my nose around in jewellery purveyors to see what treasures they have unearthed so I thought I would give you a lowdown on a couple of my personal favourites.

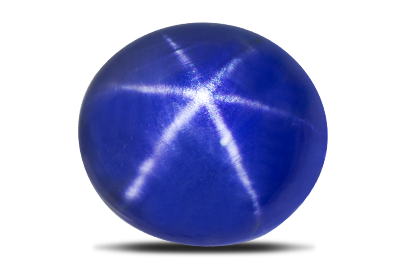

In case you’ve been hiding under a rock (ahhh, there’s a litany of puns I’m aching to use in this article!), Sri Lanka’s blockbuster gemstone is the blue sapphire and Sri Lanka is now the world’s main source of high quality ones. The finest Sri Lankan blue sapphire is a velvety mid-blue, also known as “cornflower” blue, with high transparency and clarity. If you see fine needle-like inclusions (known as “silk”) then pat yourself on the back as it indicates that the blue sapphire is not a synthetic. The flip side of that win is that silk can diminish the value of the blue sapphire unless it is so pronounced that it produces the effect of a star known as an asterism (star sapphire). Another possible inclusion to be aware of is zircon which destroys the stones crystal lattice and produces a distinctive “halo” effect. Whatever the quirks, I am biased. I own engagement ring set with a blue sapphire and I have to tell you that it rarely passes without comment on its beauty.

As exquisite as blue sapphires (and my engagement ring) are, if money was no object I would own a rare padparadscha sapphire. The term padparadscha is a Western corruption of the words padma raga meaning “lotus colour” and the finest is said to be the salmon-orange colour of a Sri Lankan sunset. As if further lyricism was needed, it has also been described as "a true Rembrandt amongst gemstones". Some of the lighter padparadscha tones can easily reveal inclusions but these stones are so rare that you might have to sacrifice high clarity to obtain a stone with brilliant colour. Ultimately what comprises a padparadscha sapphire is not an exact science so, to avoid getting it confused with pink or peach sapphires, get a certificate establishing that the colour of the gem falls within the very narrow agreed upon range of colours for a padparadscha.

Padparadschas are coloured by the presence of both iron (the element which gives blue sapphires their colour) and chromium (the element which gives rubies their colour)

Other sapphire hues are also available in Sri Lanka but are usually of less value although to my mind these are no less fascinating or useful and Sri Lankans are already starting to use them imaginatively.

If you’re after the fiery warmth of a Sri Lankan ruby, then unfortunately they are not as prevalent as they once were. With some luck you can still find fine Sri Lankan rubies – they have a strong fluorescence making them glow internally red even in artificial light – much like the prized pigeon-blood red of the very valuable Burmese rubies. It’s more likely however that in Sri Lanka you’ll come across ones which are pinkish in colour but with a hint of purple due to iron inclusions. If you don’t see any inclusions, then it’s probably been eradicated through slow heat treatment resulting in rubies closer to the colour of those Burmese rubies.

This is not to forget the important chrysoberyls, tourmalines, spinels, garnets, moonstones, topazes and zircons, just to name a few in the treasury of Sri Lankan gems (there’s a small book to be written here – how much time do you have?). Like the lesser value sapphires, these stones might not have the cache of the precious gemstones but therein lies their secret beauty. At a better price point, they are less likely to be enhanced with heat, they are superior to synthetics and these gems have been commandeered by creative Sri Lankan designers who are making jewellery of contemporary flair and artistry.

And that, my friends, is where the story of Sri Lankan gems really begins to take shape. Stay tuned.